The Marangu Cultural Tour

“This is a Yuka leaf,” said Steve our tour guide, plucking the long thin green leaf from the stem. “The Chaga (sometimes spelled Chagga) people use these plants to separate farmers’ land.” Essentially the Chaga people, who live on the south and south easterly slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro, and are fantastic farmers of coffee and bananas, divide up their farmland using these plants. The Yuka plant (I cannot be sure of the spelling as this is the local name for what some googling has shown me to be the Masele plant) marks where one farm ends, and the next begins and it also marks where farmland ends and public walking paths begin. It’s like a natural fence. Steve had picked us up at 8.30 in the morning from Rafiki Backpackers where we were staying in Moshi, Tanzania, to take us on the Marangu Cultural Tour. We had driven for around 45 minutes past the gigantic looming, yet rather shy (it always seems to be hiding behind clouds) Mount Kilimanjaro and were around twenty minutes into our walk to the Chaga Caves when Steve spotted the leaves.

According to Steve these leaves were used by members of the tribe to seek forgiveness from others. “If you’ve wronged someone,” Steve continues, “maybe you drank too much banana beer and started saying bad things to someone, you use this leaf to ask for their forgiveness. You pluck the leaf and tie it in a knot like this,” Steve then tied a standard knot in the leaf and held it out for Claire and I to look at. “Then,” he continues, “you go to that person’s house before they wake up, early in the morning and you leave the leaf on the floor outside. But, you cannot go alone. You must take someone with you who is older and wiser. Once you place the leaf on the floor you knock on the person’s door. Then, when they answer, you apologise for what you said or did and you ask them for forgiveness. If they step over the leaf, then they are forgiving you. But if they do not then you are not forgiven. And if they don’t forgive you then the older person will try and speak to them to see what is wrong.”

The Chaga tribe is the third largest indigenous tribe in Tanzania and they originally fled from north of Kilimanjaro in modern Kenya due to conflict around six hundred years ago. They originally settled on the north side of the mountain, however, after drought and the threats associated with a lack of water, they continued to move until they arrived south of Kilimanjaro. They are the only tribe to have traditionally settled on the slopes of the mountain and are still living there today in a number of villages. One village was Marangu, Steve’s hometown. Marangu is a large village spread out around the hills and valleys. It is also incredibly picturesque with winding walkways flanked on either side at times by neat and tidy grass. The tall trees and shrubs, combined with the cooler temperatures (compared to Moshi where we had come from) painted the entire area in a hundred shades of green. Huge banana and coffee farms, the main exports of the Chaga people, are everywhere.

Apart from becoming fantastic farmers and being able to work steel like few others can (more of that later), the most fascinating achievement of these industrious and ingenious people has to be their caves. But first a little bit of history. The well known Masai tribe of nomadic cattle herders and fantastic warriors spread over Kenya and northern Tanzania and had stumbled into the Chaga lands. After discovering that there were people up in the mountains, with plenty of natural resources at their disposal, the Masai, who were without enough food and water to survive due to continual droughts, began attacking the Chaga tribespeople. They would steal their cattle, food resources and even took slaves. The boys would be snatched by the Masai and used as slaves and the women would be used to breed, utilising the bigger, stronger Masai men to help produce equally impressive warriors in the future. However, after the Chaga male slaves began revolting against their oppressors, once they had reached a certain age, the Masai decided not to take any more male slaves. The next generation of conflicts ended with the Masai maiming the young boys, but still taking the women for breeding.

So, what were the Chaga people to do when the Masai came into their lands around three hundred years ago? They weren’t able to match the Masai warriors and were dying in droves, losing their women as slaves and losing their cattle and other resources to this rival tribe. Well, the Chaga people decided to build a labyrinth of tunnels in the mountain where they could hide. Four kilometres of tunnels, wonderfully hidden from view, that would offer them a refuge. Then, once the Masai moved on, they would come back up to the surface and carry on as normal. We had been told about these tunnels, and were looking forward to seeing them up close. But what we weren’t expecting was the level of sophistication in place and the sheer brilliance of the Chaga people to avoid detection and defeat once inside the caves.

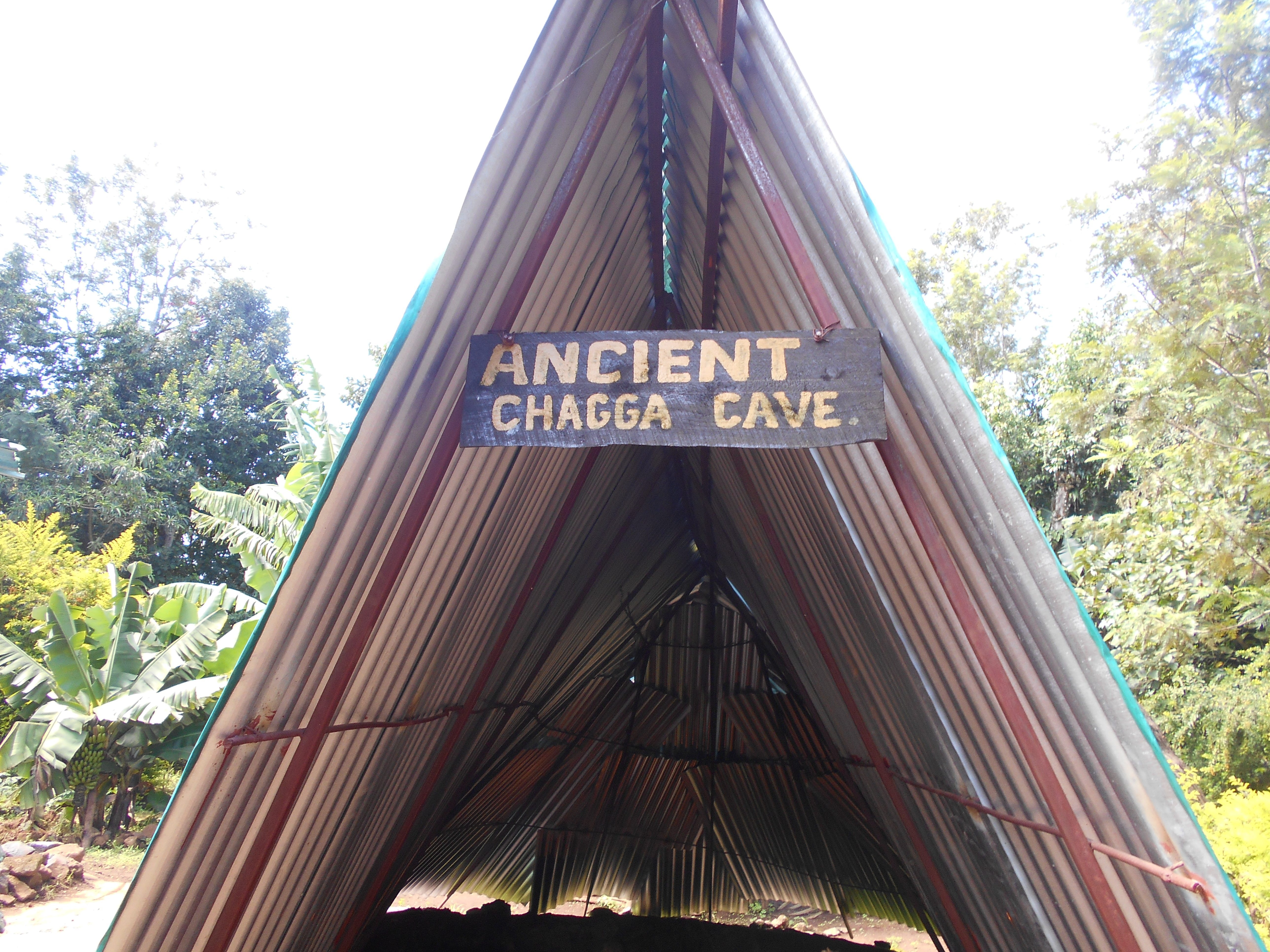

The entrance to the Chaga Caves

We turned up to the caves in the middle of the morning. The sun was shining and we’d enjoyed our hour long stroll through the luscious greenery of Marungu village, listening to Steve’s wonderful insights into the wildlife and Chaga traditions. As we arrived Steve introduced us to Daniel, the tour guide at the caves. Though Steve referred to him simply as ‘Rasta’. Daniel is a wonderfully warm, kind man, with quick whit. After introducing ourselves and having a brief chat we were making our way underground.

As soon as we were in the opening to the caves Daniel began. “When they were hiding you wouldn’t see this entrance to the caves. They would cover it with a grass house, a traditional African house and here they would place a wooden floor, scatter some dried grass over the top, and some scattered bull shit, so the enemies would assume it was a house for cows.” This was the first of many cunning moves by the Chaga people to avoid having their caves discovered by the Masai people.

Once they were inside the caves, in the entrance tunnel, no lights were allowed. The tunnel is narrow, narrow enough for you to touch either side as you walked along. Then, around ten metres in, the cave widens slightly and on one side there is a little alcove. In this location three Chaga guards would stand. Men who understood the words of the enemy would be chosen and they would wait there to ambush any Masai who had wondered into their underground fortress. But how do you know if the person coming your way is the enemy or a friend? Well, this is another genius move. The Chaga people were told never to enter the cave with a flaming torch, they were only to enter in complete darkness. Therefore, if anyone came in with fire on the end of a stick to light their way, the Chaga men would jump out with their spears and put an end to the intruders instantly. “If someone comes in with fire on a piece of wood, that’s not a Chaga and the guards smash them. The Chaga comes in and out like a butterfly,” adds Daniel.

Chaga people entering the cave would walk along with their hands on either side touching the walls. Then, when the cave widens to the point where they could no longer reach the walls (just before the alcove containing the waiting guards) they would stop. “When you get to this point and the walls are too wide it’s a hole kind of. Actually, for them it’s not a hole, it’s a signal. If you can’t reach the edges then you stop where you are going and take one step backwards in darkness. Then you mention the codeword and the men give you a reply if the codeword is correct. Wrong codeword, no reply and you would get a trick question about your family members inside the cave. And if you know the answer to this trick question about your family members properly, it means you are located with them and you know them and they will let you in and out without seeing or touching you.” This fascinating routine was a wonderfully clever method of making sure that you don’t let anyone untoward into the caves, whilst also avoiding detection by preventing the use of any flames or lighting. Luckily for us they have now added some light bulbs throughout.

Daniel and me.

These caves would be home to over 60 families, each with their own living spaces and rooms for storage of cows and other supplies. The living areas were rounded rooms of sorts that were a few metres across. They had cooking areas for preparing food, but there had to be somewhere for the smoke to go. So, they created chimneys leading up through holes out of the tops of the caves. But this leads to another problem. What if the Masai saw the smoke billowing up out of the holes? Would that not reveal their location? The Chaga thought of that, so on top of the holes, they built filters. They used small rocks piled one and a half metres high and four metres wide like a termite hill. These rocks would filter the smoke allowing it to exit the caves in small invisible particles with no smell. They would, however, only be able to have fires burning for three hours as they worked out that any longer than this and the smoke would start to become visible.

“Can you just look up here and tell me what you see,” says Daniel to Claire, pointing into a little nook in the side of the living room. Claire says that she can see some light up through the hole. “This is a ventilation hole and it is located in every room for families.” Again, wouldn’t this lead to them being heard perhaps by passing Masai? Or wouldn’t the hole in the ground be a signal that there was someone hiding beneath? And wouldn’t animals or ants come down and cause problems? Well the Chaga thought of that. “On top the people planted species of plants disliked by animals and ants because they are poisonous,” continues Daniel. “If animals or ants feed on it they get sick or die, so they stay away and the Chaga have a vent hole covered by a big bush. However, after a while the Masai learned this trick, so when they came to attack they didn’t go into the cave, they would wait until night time, move the bush and then cover up the vent hole so they would die slowly.

So the Masai had learnt of their tricks. The poisonous bushes were a signal of caves below. But that didn’t deter the quick-thinking Chaga people.

“The Chaga were ahead of the game and planted a lot of these bushes everywhere. To give them a crazy hard time.” Claire and I laughed at the brilliance of their methods, Daniel continued: “Eventually they discover one of these holes again and they aren’t sure if it is a vent hole. So they put a wooden stick through to check and nothing comes out and the stick disappeared down the hole. They had no answer. So the Masai started to put stones down the hole. The Chaga people brought water container, a clay pot. A big one with thirty or fourty litres capacity full of water and they catch the stones, which splashes. The Masai throw several stones and then give up assuming it’s an underground well and they leave and they go.” It seems like at every turn, after sitting on the brink of discovery or defeat, the ingenuity of the Chaga people was able to save their lives. Their brilliance didn’t end there.

One of the main reasons the Chaga people were fleeing from the Masai was because their rival tribe was after their cows. So they also hid their cows deep underground with them. “But in the cave,” says Daniel, “cows make noise. And you can’t tell the cow, ‘please cow shut your big mouth’. So what you have to do is silence the cow. The Chaga would send warriors to the river and the warriors would bring back volcanic ash, which was dusty with plenty of salt and sulphite in it. They would bring it into the cave and add it to the cow food and the cow would eat it and like it. And because of the salt, after a few hours the cow would get highly dehydrated. So they would bring too much water for the cow, triple the amount, and the cow would drink and not stop because of too much dehydration. Thirsty thirsty. The cow makes herself big and heavy and she would sleep down flat on the floor and make no noise because of too much weight of the water. And that was how they would silence the cow down.” And what would happen if the cow wasn’t quiet the next day? “And if this cow is a stupid cow, and it makes noise again the next day after all that treatment, then the Chaga doesn’t like it. They catch it, kill it and get barbecue and there is no more noise from the stupid cow.”

There were plenty of other stories that we were told from how they disposed of the bodies of their enemies late at night into the river and cut up into pieces to avoid detection, to how they survived a flooding and a chemical attack by the Masai. Despite all of their brilliant techniques for avoiding detection and other ways of dealing with those intruders who did make it into their caves, life underground was not ideal. Most of the adults wouldn’t be able to get proper sleep through fear of being found and slaughtered.

Eventually, as times changed the issues between the two tribes fell away and Steve was happy to tell me, when I asked, that they were now friends or “rafikis” and were no longer fighting.

Steve took us from the caves down to the beautiful Ndoro waterfalls. We walked down a windy path until we were right at the base of the falls, being lightly dampened by the spray. Then, after hiking all the way back to the top we made our way to the Chaga Museum. However, the museum was closed due to renovation, so Claire and I sat with the museum guide on someone’s front porch as he relayed to us the history of the Chaga people. We were joined on the porch by a number of other locals and whilst the emphatic Edward, the museum guide, told us all about the early history of the Chaga tribe and what they farmed, a lady appeared with a cup of banana beer. This fermented drink is a local’s favourite and came in a round cup on the end of a stick. It was then passed around for everyone to have a swig. This thick, mulchy drink full of millet had a sharpness to it, similar to the local beer we tasted in Sipi Falls, Uganda. Whilst we were swigging away, Edward explained to us how the beer was made. Whilst I can’t say I’d ever order a glass of banana beer in a bar, I did enjoy the stronger banana wine that was brought out after. It seems that to compensate for the museum being closed, we were getting free booze. Not that we were complaining. The banana wine was similar to a scrumpy cider in taste and was much easier on the pallet than the beer. I’d most definitely have had another bottle if they were offering one.

Me and Edward.

Whilst Claire and I sat on the porch, drinking and chatting with Edward and the other locals, hearing more about the Chaga ways, Steve nipped off to get the car. When he arrived I asked if we were off for lunch. However, he felt bad about the museum being closed and decided that he would take us to see the local blacksmith. This was an added bonus as it wasn’t on our itinerary. And, the museum being closed meant that we got to sit and chat with the locals for almost an hour. No matter how interesting the museum would have been, the interactions we had, practising the minute pieces of their native Chaga language that Steve had taught us in the morning, and speaking about our travels, whilst hearing about how much banana beer they could drink in a day, was one of the highlights of our trip.

So, the next stop was the six hundred year old blacksmith where the locals made spears from steel and wood, along with other items. The people here had mastered the art of working steel centuries ago and now it’s a huge export for them. One man was sat down hammering some burning bright steel on an anvil whilst his colleague sat on the floor next to him manually operating the bellows with both hands. He made it look much easier than it actually was. When I, and then Claire, had a go, we were truly rubbish. But the blacksmith was a great place to witness the craftsmanship on display.

After the blacksmith we headed off for a local lunch, which was quite possibly the best food we’d eaten in Tanzania. We were offered up a mixture of dishes including rice, spiced lentils, a sort of beef curry, local beans, boiled pumpkin leaf, savoury local bananas in a coconut sauce and avocados. Then they brought out sweet bananas for desert. And the whole meal was washed down with a delightful fruit juice made from mangos, passion fruit and avocado. After a very busy day that lunch was much appreciated. But we weren’t done there. There was one more thing for us to do before we headed back to Moshi. We had to make coffee, from scratch, the local way!

Claire and her home made coffee

After lunch Steve took us into the garden to show us the Arabica coffee trees and told us all about how they harvest the beans before drying them in the sun for three weeks. Then, once they are dried, it’s time to make coffee. And that’s where we come in. Claire and I were going to make our very own cup of hot coffee, starting with the dried beans. As a side note I will add that whilst Claire and I did contribute some effort to the making of the coffee, most of the actual work was carried out by Steve. First off we had to grind the beans to remove their hard outer shell. The beans were thrown into a giant wooden mortar and we began grinding away with a giant wooden pestle. After ten minutes the shells had all become loosened and we (mainly Steve) then flicked the basket containing the beans up and down allowing the loose shells to scatter to the wind, whilst the beans remained where they were. The last few shells were removed by hand and then the beans were ready for roasting. The beans were roasted in a giant pot over a charcoal barbecue as Claire stirred them to avoid burning. Another ten minutes later and the smell of roasted coffee beans was in the air and we had moved the roasted beans back into the pestle where they were being crushed into a fine powder. Steve then filtered the powder, to remove any lumps, and poured it into some boiling water, where it was left for a few minutes. And once it was done the three of us sat back and enjoyed a cup of wonderful black coffee chatting away.

Comments are closed here.